JR, in the past you’ve said that you do not necessarily consider your art political. Isn’t it automatically political since it is illegal in many cases?

I think my art is political just by the fact that it’s in the street. Sometimes I like to say that my work is not illegal because I believe that even if I don’t ask for authorization from the government, I ask the people. Asking the people in the community is like organizing a small referendum. So in a way, they give me the authorization. I feel like I’m working within the constitution, but the one of the street, basically.

But sometimes you do reach out to governments as well, no?

A couple years ago we did a project in Istanbul and we tried to do it legally, but the mayor didn’t want to even meet with us. They never said no, they never said yes — they just never gave us a meeting. We were lost in the bureaucracy. So one day I was like, “Okay, at least we’ve tried.” And we went for it. I also can’t say it was not political because it was pasting random people in a large format in the street and out there that is really political. But it was nothing against the government.

“I wish I would be in the middle of all of those discussions. That’s my dream of being in every street at the same time.”

What was the government’s reaction?

The state was not really happy about it, so they sued us. But the people in the street supported us. Someone sent me a photo of a piece that the police had covered up, so I posted a before and after picture and it got retweeted all over Turkey. It became so big that the city contacted us to say they apologize and they are dropping every fine. They just wanted us to stop posting about it and then they will give us the authorization to do another wall and even pay for it. So it’s really interesting how doing something in the gray zone and involving everybody in the discussion got them to bend to allow the project to happen. I wanted to bring them to that stage.

Some of the pastings from a project you did in Berlin a couple of years ago are still visible today. Do you feel like the reaction to your art is more immediate in a place like Turkey, where democracy and freedom of speech are more restricted?

In a place where the tension is higher, some pastings get covered up right away. But my work is not there in the street to be protected. It’s there to be part of the discussion. So I’m actually fine with them being scratched, peed on, painted over, or whatever. It belongs to the people and I have to let it go the minute I paste it. It’s not there to impose on people, but rather to blend into society. Sometimes it works and sometimes it doesn’t, but it’s all part of the art process. I wish sometimes I would be in the middle of all of those discussions. That’s my dream of being in every street at the same time.

Can you get a sense of how democratic a place is by looking at its streets?

All the countries where I felt there was no democracy were the countries where all the walls were very clean — no graffiti, no posters, nothing. When no one can express themselves on walls, it’s usually a sign of not much democracy. Those are the places where I’ve been the most scared. Of course, it can be too much when everybody is writing on the walls and it feels like Barcelona ten years ago, but there’s a good in-between of that.

Why do you think the street is such an important place for people to have their voice heard?

The streets have always been a place where people can write their political message. Art is definitely part of the process for people to express their vision and in some countries it’s sometimes the only way that some messages can be passed on. What interests me the most when I travel is to observe the reaction depending on the context — the same black and white photo can be a crime in one country and a piece of art in another.

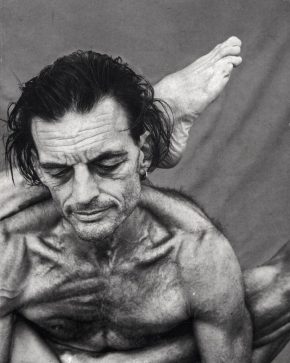

You are most famous for pasting the faces of regular people in a large format on city streets, whereas the only faces we normally see plastered throughout the city are either from politicians or advertisements.

When you see the poster of a politician, there’s the name and the party, so the answer is on the poster. In the case of my art, there’s just a face and it’s up to you to make the rest of the connection, to find out who the person is, and why is that photo on the street? And that creates a whole different interaction. Just by looking at it and what it means to you, that changes a lot.

The people you paste on the streets might represent the public better than the politicians we see plastered on our streets anyway. Is real democracy even possible in a political climate dominated by elitism?

It used to be only people from the elite that could access those positions because you had to have the money to actually make your voice heard, but it’s changing a lot. Now, anybody can be heard by millions of people. If their statement is strong enough, it doesn’t matter what background they’re from. What matters is how much it touches the people.

Your art often aims to give a voice to people who have lost theirs. How do you approach these people on the street and get them to take part in your projects?

I always approach places via the people, so either I know someone or I will meet someone that I can trust. In Brazil, for example, I was walking around the favela and I met a 60-year-old woman who asked me why I was there because that place is kind of unsafe when you are not from around there. I told her I’m an artist from France it was like I said a password! She was like, “Oh, you’re an artist? We need artists! Tomorrow just come to see me. Don’t bring any cameras or bags. Just bring your book and tell people my name.”

“It’s their face, their message, their community. I’m just an enabler. It becomes their art project.”

And did that work?

Yeah! The next day I literally crossed the whole favela, passing kids with guns and lots of crazy stuff, just with a book and her name. When I got to her, that’s how the whole project started. Sometimes we underestimate the power of art in places, even to someone that has never been to an art museum, like those kids with guns who are not interested in art in the typical ways. They had full power over it. It’s their face, their message, their community. I’m just an enabler. It becomes their art project.

Is that also the reason why you usually step away from a project once it’s up, in order to make the conversation about the people rather than yourself?

I’ve actually been trying to figure out how to create more and more distance between myself and the projects; so that it creates conversation. That has been a really important point. To give you an idea, if I go to paste in Afghanistan or in Pakistan, for example, where the American drones fly and sometimes kill civilians, and someone else puts a big photo of a kid that has lost her parents, it’s much better than if I go there and do the project alone. Then the whole discussion would be about an international artist raising this issue. But if I don’t do it and I just give them the tools and it’s their project and they decide to do it, the focus is on them. In that case they actually even printed it themselves.

So you were barely involved?

Literally, except them using the codes of my project, I did nothing. When the media called me the next day when it hit the cover of the newspapers, I was like, “I’m in Paris, I have no idea what you’re talking about.” They see that I have no information for them, so they have to go and find this person. The discussion was much stronger because it happened from the people. When it starts from local to local, it’s much more closer to the truth, I believe, than when it’s from the global to local. And I believe local action for a local impact can also have global repercussions.

The trailer for Inside Out Project, the largest art project in the world.

And then with your Inside Out Project, which became the biggest art project in the world, you took it to the extreme. The project was completely out of your hands and you let people choose which photos should be used and where they wanted to paste them.

People always say, “This project needs to happen in this or that poor neighborhood,” but I’ve always worked with people, no matter if they are from a poor or a rich neighborhood. So I wanted to see where this would happen if it was in people’s hands and it happened in 130 or 140 countries around the world in more than 20,000 cities, places I would have never gone to! I’ve seen amazing Inside Out projects in Switzerland in a retirement home because they wanted people to see that they’re still there and alive — and then in Pakistan and places where people are fighting for their lives. Both are just as important for me.

Do you think that by taking your art to the street, you are democratizing it?

Art isn’t just owned by the market and the curators and the galleries and the collectors — of course, there’s one original painting owned by the museum or the collector and that’s fair. But if I want to have it in a book here, or print it, or frame it in my house, or have a poster of it, I can still enjoy that piece. It doesn’t matter. I guess in my art it’s the same. I just went into the streets and pasted and shared the real physical piece with people. No one can own it; it’s just there in the street.

Comments