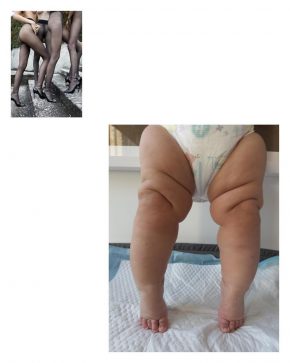

The Hijras (trans people) exist in extremes; seen as semi-sacred to the country and yet forced to live in segregation. Photographer Raffaele Petralla captures how they’ve created their own community

Finding a place in society based on sexual orientation and belief systems, continues to be an ongoing struggle – one that is sadly felt worldwide. But, what if that ‘place’ is predetermined for you through governmental legislation and without compromise? This is the reality for the Hijras (trans community) in Bangladesh, where homosexuality is still classified as a pathological condition or disease deserving of life imprisonment. Horrified by the treatment of the LGBT and trans community in South Asia, and more specifically in Bangladesh, Raffaele Petralla undertook a project in which he travelled across the country photographing those who felt the effect of these laws most intensely, in an attempt to highlight the regressive and the aggressive legislation which continues to confine the freedom of gay and trans individuals.

While recently trans voices have been heard more loudly and clearly than ever before, Petralla’s interests rest not with the high-profile activists but with the underrepresented. “I don’t want people to neglect the voices of segregated minorities, like the Hijras. The trans-community here in Bangladesh live in a state of constant secularisation, they are perceived as a third sex, and they are treated like one too.” However, there is also a deep-rooted sense of hypocrisy attached to the word ‘Hijra,’ or more specifically the role of the Guru, who is in one moment separated from society and the next associated, by ancient tradition, as a ‘semi-sacred’ influence.

The Third Sex of Bangladesh was produced shortly following the murder of two LGBT activists, who were hacked to death in their own apartment block in Bangladesh. One of these activists was Xulhaz Mannan, a respected spokesperson for gay rights and the editor of the country’s first and only LGBT magazine. This murder was one of, in what feels like, an ever-extending line of brutal persecutions on freedom. Militating for change, we asked Petralla to tell us about the Hijras he met, the daily constraints they face at the hands of sexual oppression, and the important role of photographic journalism in making people aware of it.

How did you find access to the Hijras and their very secular community?

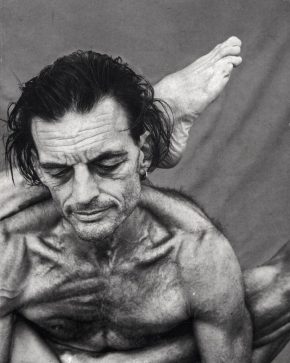

Raffaele Petralla: I had known the subject of this report, I met him on my first trip to Bangladesh. I went there initially to tell a very different story one that focused on the workers of brick factories. Walking the streets of Mirpuk-ek, (one of the most popular districts of Dhaka), I met him on the streets, and this wasn’t by accident. The Bangladeshi boys who were with me pointed at ‘a Hijra’ on the street, they were laughing loudly. I approached him, fascinated and we later became friends.

When we got home, he introduced me to some of his roommates. When we started talking I realised that their stories had to be heard. I decided to do some research and interview follow-ups. A year later I contacted the same group and returned to Bangladesh to produce the series. I spent my days with them, 20 in total, living, eating and sleeping in their small homes. I would often lay on the floor as their community space comes with so few beds yet so many people.

From first-hand experience, can you tell us a little bit about Bangladesh and how same-sex relationships are perceived?

Raffaele Petralla: Homosexuals and Hijras are forced to live together, in secular groups, usually in confined spaces – as the images show. The legislative and social situation remains very much unchanged: it is controversial, problematic and has been proven life-threatening. Although Hijras have very recently been granted some basic human rights, they are still victims of discrimination and abuse, both physical and verbal.

“The legislative and social situation remains very much unchanged: it is controversial, problematic and has been proven life-threatening” – Raffaele Petralla

Who would be defined as a ‘Hijra’ in Bangladesh?

Raffaele Petralla: Bangladesh has a population of roughly 170 million people. 90 per cent of those is Muslim. The number of Hijras estimated in line with governmental statistics is 10,000, however, it is said to be much more than this – this secret is indicative of the stigma that still comes with the status. Trans people have always been referred to as a ‘third gender’ in Bangladesh, making it clear that this group of people conform to neither social sex.

There is a great level of duplicity felt around the word Hijra, although Hijras are separated from society by the classification as a third sex, they are also by ancient tradition, viewed as being somewhat ‘semi-sacred’ and are asked to bless new-born babies through a purification process – a regime that can be traced back to Hindu mythology. This ancient practice is respected by some of the city’s most popular districts including Dhaka.

Would it be true to say there is a level of hypocrisy in attitude toward Hijras then?

Raffaele Petralla: Yes, I found attitudes were so twofold. Throughout my research and reportage, I came to find out that a lot of the man I documented, had long-term relationships with married men who secretly declared their love to ‘the third gender’ yet despised them in public.

The term ‘third sex’ suggests Hijras are still very much at the start of their fight for basic human rights?

Raffaele Petralla: Exactly, which is why I made it the title of the series. This term can be traced way back to the nineteenth century, and was first used by in a scientific context to highlight a supposed link between psychiatric mentalities and homosexuality. It was deemed pathological to have feelings of homosexuality. The hypothesis was later shelved and instead the ‘third sex’ expression was used as a concept. Changes in Bangladesh are being made, albeit small ones, but they feel a long way away from the comparatively liberal UK. The Hijras can not legally be who they want, or love who they want.

Comments