The visionary director shares a behind-the-scenes documentary for ‘Gosh’ and talks filming in a fake version of Paris with 300 Chinese schoolchildren

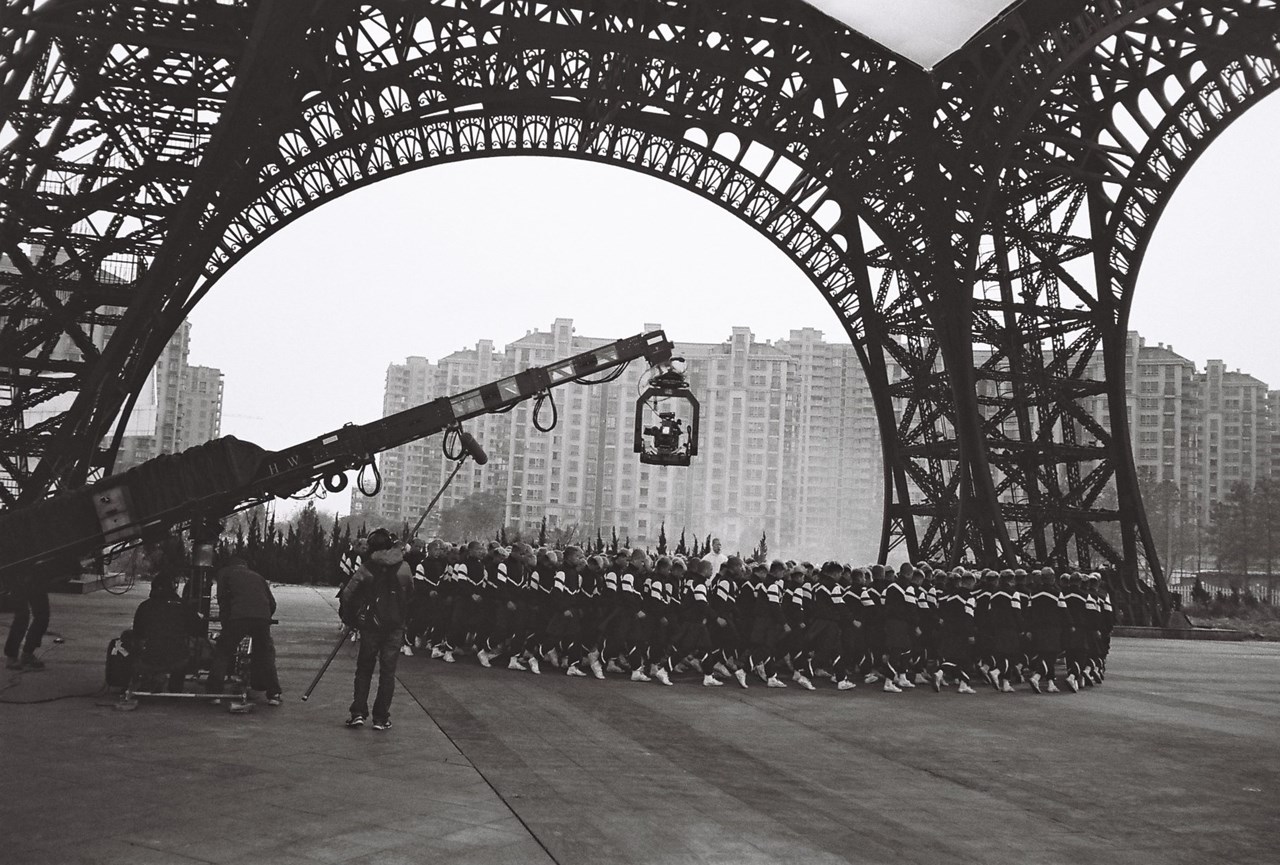

In the early 2000s, China began building imitations of western cities. It’s possible to visit replicas of English, Swiss, and Californian towns without ever leaving the country – and if you go to Tianducheng, you’ll find yourself in Paris. Tianducheng was originally conceived as a destination for affluent Chinese tourists (it boasts its own Eiffel Tower and Champs Élysées), but due to its size, location, and poor planning, the town houses only a fraction of the population it was built for. For Romain Gavras, a Parisian native, visiting the town was a particularly strange experience. “Most of the time I felt like I was on acid, basically,” the Greek-French filmmaker explains on a balmy evening in east London, “You walk out on the street and you’re in fake Paris and you have Chinese kids saying hello. The whole thing is very fucking meta, very weird, and very confusing.”

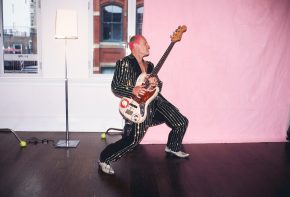

Gavras was in Tianducheng to film “Gosh”, the stunning new music video for Jamie xx. The video is a coming-of-age story that stars a black man with albinism and features over 400 Chinese teenagers with bleached blonde hair, setting them against the hyperreal setting of Tianducheng. It’s the sort of video that only Gavras could make: unlike many independent filmmakers, he likes to think big. His audacious video for M.I.A.’s “Bad Girls” depicts street racing in a Moroccan desert, while the cinematic visual for Jay Z and Kanye West’s “No Church In The Wild” shows rioters clashing violently with a militarised riot police force. What’s remarkable about “Gosh” is that it was made without using any CGI or 3D effects: as a new making-of documentary shows, what you see is what you get.

“Gosh” is Gavras’s first music video since working with Jay Z and Kanye West in 2012, though he’s hardly been idle in that time. Besides the fact that he’s had a child, he’s also created commercials for brands like Dior and spent time in Afghanistan with Generation Kill writer Evan Wright, researching for what would be his first feature film since 2010’s Our Day Will Come – an absurd, Dr. Strangelove-esque war film, as he describes it. “I’m really happy with the script,” he says, “But it’s a very, very expensive film.” That means explosions, helicopters, “all that shit” – the sort of thing that only normally gets funding with an aggressively pro-military slant. “I was a bit naive thinking that they’d love it and give me shitloads of money,” Gavras laments, “So I’ve been writing another French film on a smaller scale that’s almost finished. We’re financing it right now.”

Gavras’s films and music videos often focus on marginalised or minority groups, whether that’s literally (the Romanian gypsies featured in Simian Mobile Disco’s “I Believe” video) or metaphorically (the use of ginger-haired people in M.I.A.’s “Born Free”). Sometimes he’ll show these groups in extreme situations, and sometimes he’ll show them with extreme violence, but he never takes a moral stance. “When I see a film, I’m more interested in what I take from it than what the guy who made it wants to tell me,” Gavras says. “Fuck the guy who made it! If he wants to tell me that racism is bad, then I’m really annoyed. Fuck off, I don’t care what you think. It’s very on the nose – and boring as well.”

His refusal to reveal his intentions has often proven controversial. In 2008, he released a video for Justice’s “Stress” that showed black youth gangs from the Parisian suburbs terrorising people around the city. The uproar that followed saw him accused of racism by the liberal press, and anarchism and nihilism by conservatives. But looking at Gavras’s background, it shouldn’t be hard to see where his priorities lie – his father is Costa-Gavras, the celebrated auteur who left Greece after his father’s Communist Party membership prevented him from attending university in the country or getting a visa to the United States, and Gavras describes his upbringing as “very leftwing”.

Growing up in a filmmaking family (his sister, Julie, is also a director) meant that Gavras was always surrounded by cinema: the family house was used as a production headquarters, while his father ensured that he was exposed to the important works of postwar European cinema from a young age. Given this background, it’s not surprising that Gavras’s version of teenage rebellion was to immerse himself in pop culture: films like Die Hard, rappers like Snoop Dogg and the Wu-Tang Clan, and the music videos of Spike Jonze and Chris Cunningham.

Gavras started making music videos after becoming frustrated with short films. “Nobody gives a shit about short films,” he says bluntly, “You do a short film circuit and it’s the most depressing thing.” His breakthrough came when he immersed himself the nascent European electro scene of the late 2000s, making music videos starting with DJ Mehdi’s “Signatune” in 2007. Here, he learnt to show a lot while using very little. “When I really started in 2007, we did it for very, very small money,” he says, “Now there’s been a comeback.” If he gets £100,000 for a film, he’ll want it to look like it cost £300,000 – which is why “Gosh” looks like it cost a million bucks. “It’s kind of escalating,” he says, “It’s almost like now I don’t know. If I do another music video, I almost want it to be super simple, the most simple possible. It’s fucking tiring, this one particularly.”

How did you first get involved with the ‘Gosh’ video?

Romain Gavras: ‘Gosh’ had always been my favourite song on the album, but it had been out a year already and already had a music video. Music and music videos are very quickly consumed nowadays – it’s like it gets worn out after two months – so I liked the idea that this was a music video that already had a music video, and that had been out for a year. It didn’t have the pressure. At the end of the day, it’s really hard to get that level of money – it’s almost impossible, especially for an artist like Jamie.

Yeah, it’s not a radio song, there are no lyrics, it’s on an independent label, it’s already got a music video, and it’s a year old. That’s a bit of a gamble.

Romain Gavras: There were no questions asked about anything – I was literally there on my own. The thing is, we really needed double or triple (the budget to make the video). There’s never enough money.

Was there an initial idea for the video itself?

Romain Gavras: There’s different ways of explaining it. One way of explaining it could be like a white guy that is actually black – it starts in a purple room, and then he drives a blue car in a grey environment, and he’s surrounded by kids with black shoes and yellow hair. It could be said like that. But also, in my head, it was almost a process. It came about when I saw the pictures of the fake Paris in China. Everyone is talking about cultural appropriation and I was like, ‘That thing is the most insane fucking cultural appropriation.’ It’s almost like you don’t put it on a moral level – it’s not Iggy Azalea singing like a black woman, it’s fucking insane. It’s like a cultural appropriation vortex.

I almost saw (the video) like a coming-of-age journey through a world where cultural appropriation became so insane that you need spirituality in order to elevate (yourself) from something where culture makes no sense. Somehow, spirituality is where that kid (in the video) is going to find sense. It’s like when you leave your friends, when you’re in high school, and then you’re going to go to the big town – that kind of coming-of-age type of narrative. And this why then they all circle him and he’s detaching himself from his other group of friends, and then he becomes his own prophet. But really, he doesn’t elevate himself, it’s the camera that elevates – so it’s the old thing where he doesn’t change, it’s the perception that we have that changes. This was the intellectual process I had making it.

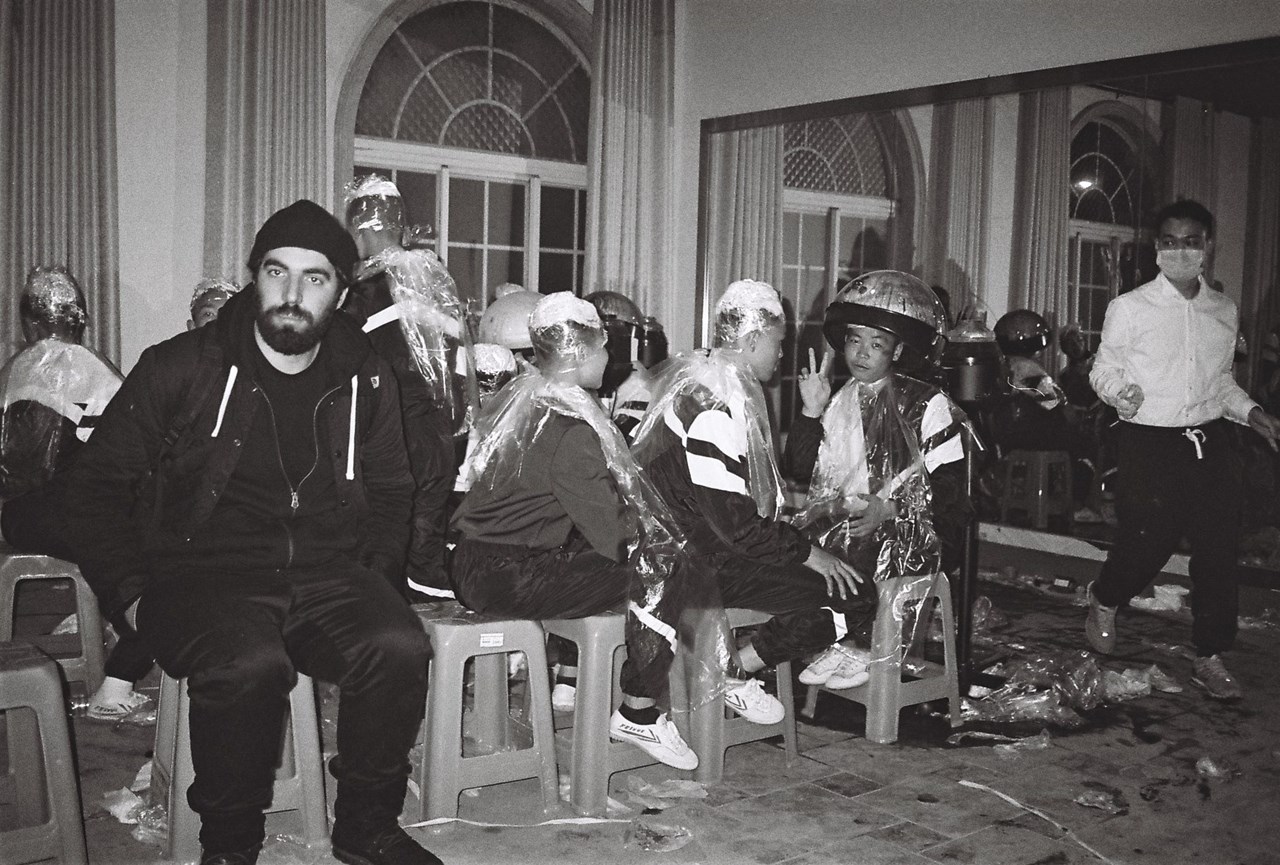

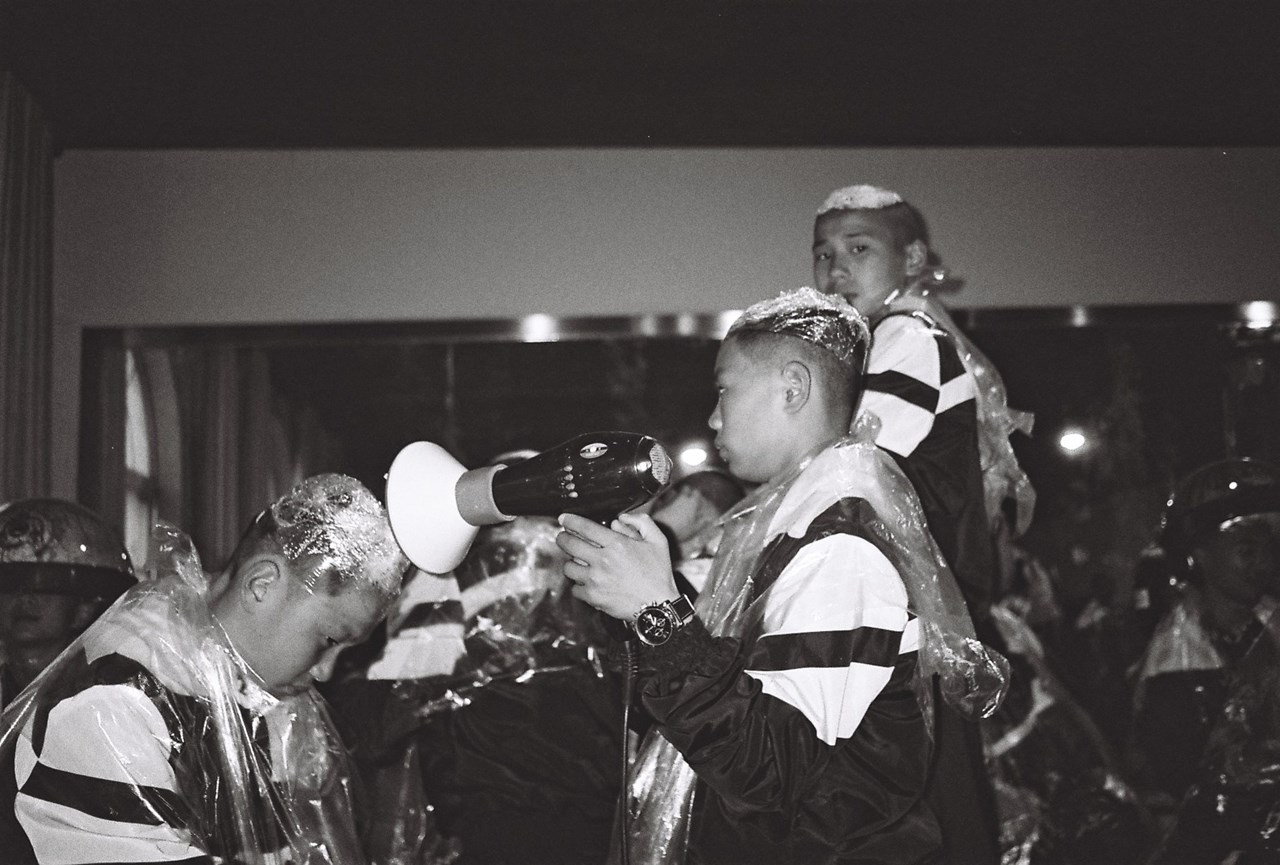

Sometimes, it was more like I had a dream that when we were there that everyone was blonde in China, so the next day I went to the crew, ‘Let’s bleach all those kids blonde because it will look fucking cool.’ So sometimes it was intellectual, and sometimes it was more intuitive. Obviously, bleaching 300 kids blonde will be fucking cool, you know?

So the blonde hair was just an idea you had on the day? How receptive were the kids to that?

Romain Gavras: The kids were fine! I wanted really synchronised movements, so I was looking into gym schools, karate (schools), kung fu schools – and we found them in a Shaolin school. So then there was negotiation with the the bosses of the school. They said ‘We’ll allow you to bleach them, as long as you put them back to a dark hair colour. And you can only bleach them one day before, because we don’t want to pervert them too long.’ It was a struggle, because how the fuck do you bleach (the hair of) 300 kids? I called all the super fancy agencies that I worked with on commercials, and they were like, ‘It’s impossible, you’ll never do it.’ We found a kid in the town we were in who had a hair salon, and he was like, ‘I’ll do it.’ He brought 40 hairdressers, and in 12 hours we’d bleached all of them. With kung fu schools, there are poor families that send their kids there, but there are also super rich families that send their kids there for discipline. So you have kids from across the board, and they were all loving it – for them it was like the holidays, going out and smoking cigarettes and looking for trouble.

How did it feel being in a fake Paris, given you actually grew up in Paris?

Romain Gavras: Well, it felt very fucking psycho. The whole trip was really weird. I stayed a month there. The fake Paris had a fake Versailles hotel which we were staying in. It was supposed to be an upper-middle class heaven, but it never really took off. It’s half-inhabited, like a ghetto (version of) central Paris – like if the estates of the outskirts of Paris were brought next to the Eiffel Tower, you know? I don’t know what to make of it.

“I saw the pictures of the fake Paris in China. Everyone is talking about cultural appropriation and I was like, ‘That thing is the most insane fucking cultural appropriation.’ It’s almost like you don’t put it on a moral level” – Romain Gavras

What’s the name of the actor who plays the main character?

Romain Gavras: His name is Hassan Kone. We found him in Paris. He’s 17, still in high school. He was amazing because it was a first time thing, he was street-cast. At first – and this is what I was saying about the process – I didn’t want to cast him. I just went to my casting director and I was briefing him to find somebody interesting to be the main character, so there was, like, 20 guys to go by. I didn’t want just an interesting face, I wanted somebody that has an emotion that’s really strong. And there was that kid. He was the only albino (in the casting), and although I was not looking for that, I thought ‘Oh, he’s really interesting. He moves me, I don’t know why, but he moves me.’ So then when we were in China, we looked for Chinese albinos – which is not easy to find because they’re not accepted socially. We found them through Chinese Facebook links, and I ended up in a party of Chinese albinos. They hang out with each other, and some of them were great, and we cast them for the video.

So casting people with albinism wasn’t your original intention? Because I read an interview with you a few years ago and you said you originally had the idea of using albino people for the ‘Born Free’ video rather than ginger people.

Romain Gavras: Oh, was it?

Yeah, you said that in an interview.

Romain Gavras: I don’t even remember. Maybe it was harder to find at that time. It’s not even like a hair/complexion type of fetish or anything, it’s more that – especially with small formats – it’s good to talk in allegories, otherwise you’re too on-the-nose. Whereas if you kind of look back and put more of an allegory type of grammar in it, then it’s more timeless. But it was not even calculated.

You don’t generally feature musicians in your music videos…

Romain Gavras: The thing is, I don’t necessarily see music videos as a promotional thing. I’d rather kill myself than make a normal music video for YouTube with Bono singing in front of the camera. That’s my vision of fucking hell. Most of the videos I’ve done were for friends. What’s good is that you both benefit from it, because they have an interesting video, and you have more exposure for the stuff that you make. I think it’s interesting to put an artist in front of the camera when the artist is an interesting performer, or it’s interesting to film them – it’s really hard, but it’s amazing if you manage to translate it.

I was wondering how much discussion you actually have with the musicians about the videos when they’re not in them?

Romain Gavras: Oh yeah, there’s a conversation. It’s never me being completely self-centred. It needs to go with the image of the band. Most of the people that I work with are clever people, and then it’s something about trust.

Are artists generally receptive to the ideas that you have?

Romain Gavras: I’ve always been lucky, I guess. I think the only idea (I’ve had turned down) was kind of a love song between two huge artists. (My idea for the video) was a love song between ISIS dudes and a hostage. So the girl was a hostage, and the guy was an ISIS dude, and there was a confusing love song between them with the whole imagery of the orange jumpsuits and everything. I don’t know why they didn’t like the idea. Also, if massive artists call me to do stuff, I usually don’t go there because I know I’ll be fucked over, either by the artist, their entourage, management and all that. I never really engage with people I’m not comfortable with.

“I don’t necessarily see music videos as a promotional thing. I’d rather kill myself than make a normal music video for YouTube with Bono singing in front of the camera. That’s my vision of fucking hell” – Romain Gavras

A lot of your videos focus on marginalised groups. Why is that a subject you often find yourself returning to?

Romain Gavras: Since 2007 – with the Mehdi video, the Justice video, the Last Shadow Puppets video, and the Simian Mobile Disco video – I wanted to have really strong, European icons. At the time, music videos were either super low budget English indie videos – kind of like fake (Michel) Gondry with papier mâché or whatever; super low budget – or they were the most glossy, American, Hype Williams type of thing. Which is good, because I like Hype Williams. So in my head, it was more like, ‘Let’s find the youth in Paris, let’s find people who like tuning cars, let’s find the gypsies in Romania.’ Really European icons.

With the marginalised thing… I see a lot of videos that are almost like poverty porn, you know? And I’ve always wanted to transcend that kind of shit. This is why I’m talking about icons – because if it’s the sad thing where you’re just like, ‘Oh, look at those crackheads,’ then it becomes something a bit like porn. But when you put it in a cinematographic form, it becomes more iconic. For example with the ‘Stress’ video, it means you transcend that shit and you’re not in the category of whether it’s violence porn, or poverty porn, or whatever.

I think about the violence thing a lot. It’s really subjective what violence is. Katy Perry videos are super violent. The one where she goes to the army because she broke up with someone? In my head, I was fucking shocked, and nobody was shocked by any of it! Teenagers listen to that shit. Are they going to enrol themselves because they broke up with a girlfriend, and then go to fucking Iraq and get killed? It was the most confusing shit I’ve ever seen.

Do you consider your videos political?

Romain Gavras: Yeah. Again, I think everything is fucking political. Everything is political because it pushes a view on culture. But I play with stuff that is more symbolically political, I guess.

Comments