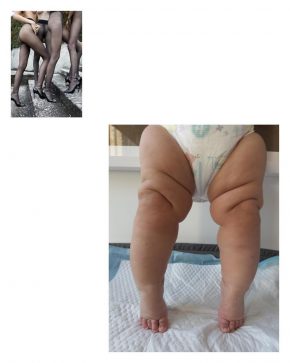

In “Faces Places,” Varda’s work with JR becomes, in its own way, iconic of itself—his murals are transformed, here, into symbols of her own artistic passion.

Photograph by Cohen Media Group via Everett

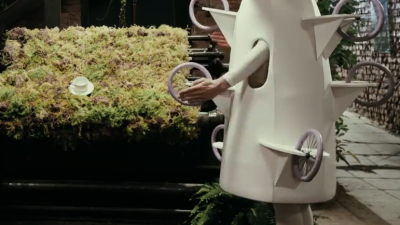

The original French title of “Faces Places,” the new film made jointly by Agnès Varda (born in 1928) and the photographer and muralist JR (born in 1983), is “Visages Villages,” meaning “Faces Villages,” which more precisely reflects the film’s substance and the directorial duo’s intentions. They travel in JR’s van (equipped with a photo booth and a large-format printer) to small towns in France, which are as infused with nostalgia as are American small towns, and which are similarly threatened by the economic and social forces of modern life. In the movie’s first set of extended encounters, in a former coal-mining town, the filmmakers speak with a woman named Jeanine who’s the lone holdout in a row of miners’ homes that’s soon to be demolished, and then with neighbors from the town who lovingly describe the ways of life that have vanished from the town along with the mining industry. What Varda and JR do with their filmed knowledge is what distinguishes it from the familiar round of investigative documentaries: a headshot of Jeanine, taken in the van, is blown up dozens of feet high and pasted by JR and his crew to the wall of her house, magnifying and honoring her on a scale usually reserved for public and historic figures.

The filmmakers’ meetings throughout France result in similar large-scale projects that are based on the work of JR (whom Raffi Khatchadourian profiledfor The New Yorker, in 2011) but are in keeping with Varda’s explorations and encounters in previous personal-documentary work, including “Daguerréotypes,” “The Gleaners and I,” and “The Beaches of Agnès.” The subject of “Faces Places” is the heroism of daily life, the recognition of the daily labor and struggles of factory workers, farmers, waitresses, and, for that matter, women over all whose private roles in sustaining the public lives of their male partners go largely uncommemorated.

Their encounters include a farmer whose technology-aided labor enables him to do, alone, in what he calls an “antisocial” way, the work that he used to do in the company of crews, and a mailman who now delivers mail by truck and reminisces about the years when he did so by bicycle and schmoozed with farmers while on his route. They speak with a dairy farmer who burns off his goats’ horns in their infancy in order to prevent them from fighting and uses electric milking equipment; they speak with another one who wants to “respect the animal,” to “leave them intact,” letting the goats roam free and milking them by hand. (Celebrating that farmer’s philosophy, Varda and JR put a photo mural of a goat with horns on the wall of a local factory.) They visit a chemical factory and induce the workers (and even some management) to do drolly choreographed group photos that JR and his crew muralize; they go to see three dockworkers—all men and members of a famously militant left-wing union—and interview and photograph and monumentalize their wives.

In the film, Varda and JR create murals of some of their interview subjects, magnifying and honoring them on a scale usually reserved for public and historic figures.

Photograph by Cohen Media Group via Everett

Varda—who does most of the talking with the people they meet—doesn’t ask them about their politics. She doesn’t need to. Almost all of the people they meet are white and, for that matter, living in what appears to be conspicuous isolation from nonwhite people. It’s inevitable that, in a former mining town or a dwindling farm region, some of the people who cheerfully agree to be filmed will be supporters of France’s far-right National Front, and will harbor the prejudices and hatreds that it fosters. But the politics of “Faces Places” is a trans-ideological vision of curiosity, empathy, and dignity, and it’s as much a politics of aesthetics, in which the documentation of private lives overlooked in the media and the arts breeds a feedback effect, turning the film’s subjects into public figures, subjects of art and media discussion. The sense of loss that many of these subjects confront, the sense of resistance to unwelcome change that others display, makes “Faces Places” essentially elegiac, a snatching of vitality and consolation in a race against the ultimate loss and oblivion, death. Yet the movie remains warm, lighthearted, enthusiastic, even celebratory. More than a cinematographer or a photographer, more than a documentarist or a narrative artist, Varda is an iconographer, whose stories and explorations, recollections and encounters, are magnified into images that are, in effect, devotional. Whether festive or mournful, tragic or comedic, they embrace the fullness of experience and emotion with a fervent grandeur, which is why, in “Faces Places,” her work with JR becomes, in its own way, iconic of itself—his murals are transformed, here, into symbols of her own artistic passion.

As engaging as the early encounters in “Faces Places” are, the movie doesn’t reach full gear until midway through, when Varda herself, with her reminiscences and her confrontations with daily medical inconveniences, becomes central to the film. It happens because of fish, and it’s done through some deftly associative editing. JR has posted a huge image of a fish on a water tower perched high above ground. He bounds up the tower’s spiral staircase to see the image up close, while Varda takes the steps slowly and can’t make it all the way up. Her pause is followed by a flashback to the fish market where they found and photographed their subjects. Varda wields the camera herself, and her whimsical closeup of the eye of a monstrous-looking monkfish cuts to a closeup of Varda’s own eye, its lids held open with medical prongs during an ophthalmological exam. She gets an eye injection and, of course, mentions Buñuel’s “An Andalusian Dog”—and then she and JR stage an outdoor theatrical scene to commemorate the experience of her deteriorating vision.

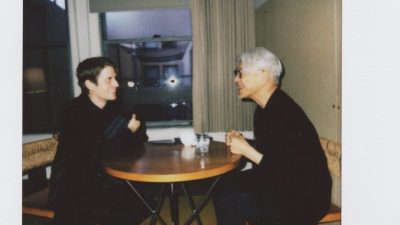

JR’s presence is as integral to “Faces Places” as is his art, both in the humorous warmth of his encounters with the people who participate in the film and in his frank and jibing banter with Varda; with him, Varda unsparingly and good-humoredly depicts the effects of age on her body and unstintingly discusses her serene anticipation of death. Though JR’s own personal history comes briefly into play in the film, he’s largely a foil to Varda’s own literal and metaphorical excursions into personal history, and he plays the role devotedly. One of the movie’s most powerful sequences slips from the aforementioned goat mural to Varda’s own photograph of a dead goat from the start of her career, in 1954. It leads both to her extended recollection of one of her models, the late Guy Bourdin, himself a photographer, whom she commemorates with a visit to his house, another to the site of one of their photographs, and to an extraordinary, calculatedly ephemeral mural of him by JR that’s washed away with the tides.

Varda’s own artistic history, as she evokes it in “Faces Places,” was influenced by one especially crucial figure: the director Jean-Luc Godard. She talks about him at the start of the film, when she tells JR—who refuses to take off his sunglasses—that Godard, when they were younger, refused to do so as well, and that she made a film in which Godard acts and in which, for her, he agreed to take them off. (A clip of it is shown in “Faces Places.”) She and JR restage a joyful parody of the famous scene in Godard’s “Band of Outsiders” in which its three protagonists run through the Louvre—Varda, poignantly, is in a wheelchair that JR pushes at top speed. And the climactic scene of “Faces Places” is Varda’s and JR’s planned visit to Godard in the Swiss town of Rolle, where he has been living for about forty years.

Quick background: Varda and Godard have known each other since 1958, when Godard, a critic, was reporting from a festival of short films in the town of Tours in which she had two films. (That’s also where Varda met the director Jacques Demy, whom she married, in 1962.) She described their friendship to me as she discusses it in “Faces Places”—she, Demy, Godard, and Anna Karina (the actress who was also Godard’s first wife) met for lunch almost every Sunday at a Montparnasse restaurant specializing in crêpes, and the four of them spent a memorable vacation together in a villa near Nice. What’s more, not only did Godard and Karina act in a film-within-a-film included in Varda’s second feature, “Cléo from 5 to 7,” from 1961—the film was made because Godard, whose first feature, “Breathless,” was a financial windfall for its producer, Georges de Beauregard, recommended her to him. (Spoilers follow.)

On the train to Switzerland, Varda and JR discuss Godard and his famous, and infamous, idiosyncrasy. Varda calls him “unpredictable”; JR asks why; Varda says, “Because he’s very solitary; he’s a solitary philosopher, he created a cinema, he changed the cinema by himself. His films are very beautiful. He’s an inventor, a researcher. The cinema needs people like him.” How unpredictable Godard is becomes clear: he doesn’t show up for the appointment, and instead leaves a note for Varda, written in marker on his glass door. (Incidentally, a very similar thing happened to me in 2000, when I visited Godard at his office in Rolle, for a New Yorker Profile I was writing.)

One of the crucial distinctions between the films of Varda and those of Godard is that her past surges forth into her films with a sense of equilibrium, attachment, and gratitude, whereas Godard’s past enters his films with a sense of destabilization, irresolution, and regret. The memorious inner landscape of Godard’s films is one of incompletion, guilt, and ruins; that of Varda’s films is one of the enduring, the venerable, the fulfilling. Godard’s films are burdened with the past; Varda’s are enriched by it. (Unless, to put it more simply, Godard, in not showing up, wasn’t thinking of Varda but of himself.) Varda is both hurt and angry when her longtime friend stands her up; she calls him a “dirty rat” and tearfully leaves him a curt, frank, but nonetheless tender note. Then she sits and talks with JR on a bench on the shore of Lake Geneva, just a quick walk from Godard’s home, bitterly and painfully and inconclusively discussing his hurtful behavior before turning her attention, and JR’s, to the beauty of the lake itself.

Comments