The urban spaces we call home don’t always give us what we need. If a sense of creativity and community is lacking, it may be time to call in the skaters.

“We were attacked for having a skateboard when we were younger,” says Paul O’Connor, a 42-year-old sociologist who grew up in a small town in Devon and has been skating since he was 11. “I remember riding my skateboard in the high street and people putting their feet right under the board – and I’d go flying.”

Skateboarding may have come a long way since then, infiltrating the highest echelons of art and fashion, but even today skaters can still find themselves demonised by broader society. From the ‘good-for-nothing stoner’ lacking in direction to the ‘loud-mouthed juvenile’ looking for trouble, skate culture has yet to shed itself of less favourable stereotypes. In urban areas in particular, the relationship between skaters and the city can be a precarious one at best.

And that’s a real shame. Largely, because the benefits that skateboarding can bring to an area are copious: from the economic to the social, its presence can have a profound, positive impact on our cities in a number of different ways. That is, of course, if you allow it.

Safety first

Take, for instance, skaters’ tendency to reduce crime in the areas they choose to inhabit. Often, skateboarders find themselves as the first wave of citizens to enter derelict, ‘no-go’ spaces where untoward activity is rife. For the riders, these areas are perfect: they’re generally left to their own devices, and usually spoilt in given the structures at their disposal.

And if criminal activity is occurring in these spaces, perpetrators don’t tend to stick around too long. Ocean Howell, a professor of architectural history at the University of Oregon and former pro skater, described skateboarders at Philadelphia’s seminal LOVE Park as the “shock troops of gentrification”, given the manner in which they swept out “undesirable” activity and made it accessible again, before eventually being swept out themselves at the hands of developers.

It’s a sociological theory that O’Connor refers to as “eyes on the street” – the idea that a healthy, happy community has people “outside, visible and doing things” – and one that’s supported by Gregory Snyder, an ethnographer whose work on urban subcultures has seen him study both skateboarding and graffiti at length.

“One of the things that skateboarding does,” explains Snyder, “is that it takes spaces that are often unpopulated, spaces that sometimes provide opportunities for crime, and it puts more eyes there. And [the criminals] get the hell out.”

Similar to the tale of LOVE Park is that of Hubba Hideout, a notorious drug spot in San Francisco during the late ’80s and early ’90s, which local skaters took to because of its two oversized sets of stairs with large concrete ledges on both sides. Back then, ‘hubba’ was the slang term for crack rock, but today, say the word to any skater anywhere in the world and they’ll lead you to a spot with that very same obstacle. When the skaters moved in, the users moved out – which would have made for a happy ending, had authorities not decided to thank them by making it a No Skate Zone.

Creative currency

“I think that the anti-skate narrative comes from a big misunderstanding of what it is that skateboarders are actually doing,” argues Snyder. “On a practical level, when you walk down the street and see some skateboarders, if you don’t know what’s going on, you just see kids falling a lot. But, if you allow skateboarding into your city, it brings with it a whole onslaught of creative infrastructure.”

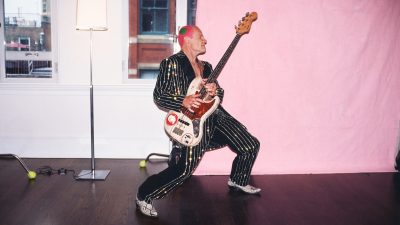

This idea of a creative class – a term first popularised by economist and social scientist Richard Florida – is useful when it comes to assessing the positive impact that skaters can have on a place. By their nature, skateboarders belong to and gravitate towards a larger creative network, made up of artists, filmmakers, writers, musicians and the like. Therefore, a city that encourages the presence of skateboarders does, by proxy, a similar thing for those who move in the same circles. While this brings obvious benefits in terms of making a place more interesting and culturally diverse, it also translates into financial gain.

When Florida popularised the idea of a creative class at the turn of the century, he did so recognising that the cities which catered to those industries – new media, tech, film – were becoming the hot spots of a new economy. So, in theory, a skate-friendly city isn’t just getting skaters, it’s getting the entire extended family – and the money that comes with it (skate shops, coffee spots and food joints that tend to crop up after them).

“People don’t understand what a productive economy skateboarding is. It’s generative, in terms of [how] it literally makes money out of nothing,” says Snyder. “Think about the production that one filmed session generates. There‘s a filmer there, the crew, writers, there’s a photographer… Skateboarding has been estimated to be a $5 billion-a-year global industry. I mean, if each city got one tenth of that, c’mon!”

Building bridges

One group who knows more than most about the way in which the city and skaters can coexist is the Long Live Southbank crew (LLSB, to friends). Formed in 2013 to save the eponymous London skate spot, they successfully guaranteed its long-term future the following year after a hard-fought campaign. Since then, they’ve been working closely with local authorities and the Southbank Centre to restore sections of the skate spot that haven’t been used since 2004. The new shared space will include an education centre focused on young people with an interest in the creative arts.

Back when the Southbank spot was under threat, it encouraged communication between skaters and authorities that would not have existed otherwise, installing in the former a sense of civic responsibility – particularly impressive, given the relative youth of many of the campaigners.

“There was a dialogue between landowners, developers, skaters and the council, which is how it should should be,” says Stuart Maclure, a 24-year-old skateboarder and project manager with LLSB who’s been riding the Southbank spot since his early teens.

“This old concept of what skateboarding should be and what a city should be is changing,” he adds. “It’s about having some kind of civil society that is proud of their city, rather than repulsed by it. If you have more voices from different communities, that makes your city more democratic. That is what cities should strive to be.”

See, despite its non-conformist roots, skateboarding has ultimately always been about community building. In fact, it’s this commitment to non-conforming that makes it such an ideal space for progressive change. As opposed to conventional, formalised team sports, it’s one of the few places that 5-year-old first-timers can do their thing alongside 40-year-old pros. For Becky Beal, a professor at Cal State East Bay whose work centres on issues of social justice in sport, it makes it the ideal environment for an urban population to express itself.

“I’ve spent a lot of time working with girl groups in skateboarding. It’s created a brand new space for girls – and gender non-binary people – to define themselves, as opposed to a formal sport that doesn’t give as much room. I think it’s more open for people to be themselves, represent themselves, self-express.”

Come together

In many ways, the best kinds of cities are fluid, kinetic ones: places that stretch the idea of what it means to be a shared space, allowing them to be a number of different things for a number of different people. In a similar way to parkour and urban exploring, skateboarding – street skating, specifically – responds to modern architecture in a new kind of way, countering its intended use and opening it up to a whole new range of possibilities.

In practice, this means that cities immediately become more collaborative. Iain Borden, architectural historian, urban planner and professor at University College London, refers to this as “performative critique”, an act of subversion that makes our neoliberal spaces exciting again.

“There’s a reconceptualisation of the city, and with that comes the critique of what we expect our cities are for,” he explains. “Increasingly these days, urban managers expect cities to be used for functionally getting around, shopping, retail – some kind of productive function. Skateboarding doesn’t do any of those. It’s not buying a mocha Frappuccino, or a baseball cap. It’s turning the city into a leisure ground, rather than a work or retail consumption ground. And that’s done through the act of skating itself.”

In the age of the individual, skateboarding encourages a coming together. Shared urban spaces become more of a collective effort, while banal and overlooked architecture assumes a second life as something productive. “Skateboarders are lovers of spaces – I think that’s a very healthy thing for an urban populus,” notes Snyder.

Looking forward

“It’s true that there are still some narrow-minded people that generalise skaters as dropouts, anti-social nuisances and failures,” says British pro-skater Chris Jones. “But from what I’ve seen, skateboarding has actually forced individuals to be more social – it’s broadened their horizons and allowed them to focus their energy in a more positive way.”

While it would be incorrect to label skateboarding as a completely altruistic, egalitarian force, the evidence supporting its nature as a force for good is widespread and readily available. From social policing to self-starting entrepreneurship, skaters provide the qualities that modern cities seek out most – and, as Iain Borden emphasises, they do that by skating.

Skateboarding can make your city more diverse and exciting while, at the same time, making it a safer place to live. It can pump money into the local economy just by encouraging creativity and self-expression. It promotes individual expression, as well as contributing to collaboration and inclusivity in shared spaces.

“Skateboarding is too damn diverse to simplify as one thing. It’s too diverse, like the rest of life, to say that everyone involved with it is either a really good egg or a really bad egg,” says O’Connor. “But I just cannot comprehend how people wouldn’t want to have skateboarders around.”

Read more stories from This Is Off The Wall, an editorial partnership from Huck and Vans.

Comments