Mr. Schapiro, why does a photograph become iconic?

I don’t know why a photograph becomes iconic, to be quite frank. You never really know when you’re going to take an iconic picture. There are many times when I thought I took an iconic picture, and it wasn’t. Or there were times when I didn’t realize it was an iconic picture until I saw it in a magazine. I did the ad for Midnight Cowboy with Jon Voight and Dustin Hoffman, and I don’t know know why that’s an iconic picture — but it is. And it’s been treated that way.

Your 1965 photo of Martin Luther King Jr. leading the march to Montgomery with the American flag behind him is another example.

That’s not a set up photograph either, I didn’t ask Dr. King to pose near an American flag. It’s photojournalism, you come in and you just try and capture what’s happening. You react to some pictures in a very emotional way, and sometimes a lot of people react to the same picture at the same time.

“Very often a picture grows on you because you see it over a long time. And that doesn’t happen as much these days.”

What do you think it is that makes a photo emotional: its content or its aesthetic?

I think it’s all in one: design and information. Today we have magazines which primarily highlight one picture which gives you information… But the great Life Magazine essays usually went for eight pages! It had a flow. And at the end of that, looking at those eight pages, you had more of a sense of the person or the event. That has diminished, unfortunately, and nothing has come in its place! When I did the Kennedy presidential campaign, there were maybe five photographers who travelled with Bobby. And what people saw was primarily the work of those five photographers.

And today, you don’t have to be a professional photographer to take a photo at any given event.

Right, everyone has an iPhone, and everyone is photographing at the same time, so it’s not individual photographs that stand out… I saw a picture four months ago of Obama which I thought was a fantastic photograph. And then it was gone and I’ll never see it again because it’s never been featured. Very often a picture grows on you because you see it over a long time, and it’s these pictures that become very popular. And that doesn’t happen as much these days.

What else contributes to a photo’s lasting power?

Well, I would say it’s to do with the photo having a degree of history in it. I did a picture of Jackie Kennedy looking out at an event in Washington instead of looking at the press and smiling. She almost never looked at the press. And there was this charismatic question of, “What is she thinking?” And it has a life as a photograph probably for that reason, but also because she is someone who people are interested in.

What can photos of political and pop culture figures like Jackie Kennedy, Andy Warhol, or David Bowie tell us about history?

They show us something about a time period. These were the people who were important in the sixties and the seventies, and many of them are still important today — whether they’re alive or not. There’s something charismatic about them: we still, even today, really want to look at them. My pictures tend to not be as stylized because my continuity is in the sense of how I feel about a person and the spirit of them.

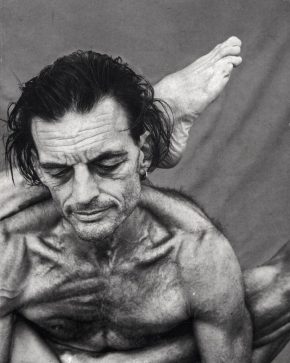

How do you go about capturing someone’s spirit?

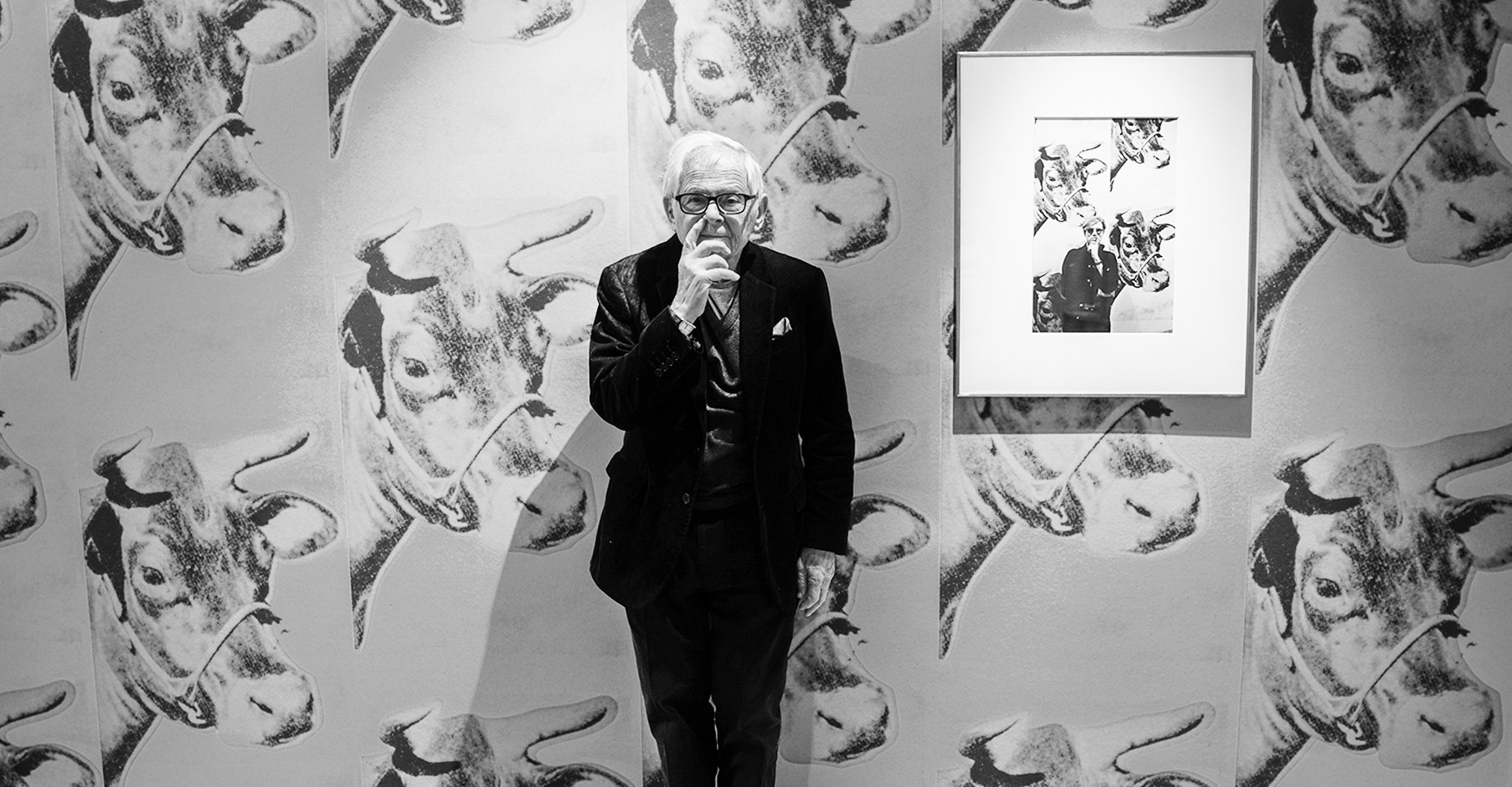

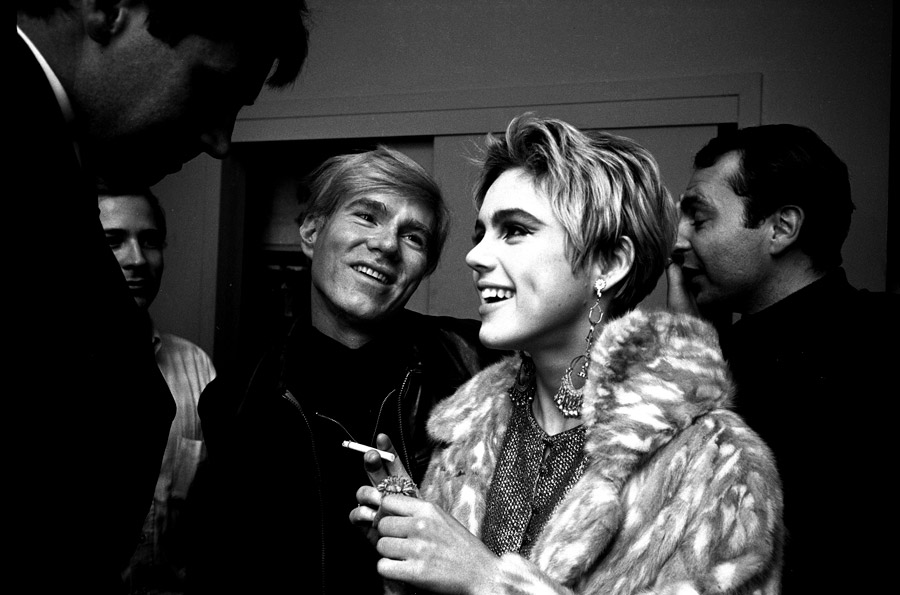

You know, I always like to be a fly on the wall if I can be. I like to wait for a moment where I saw something, or we would be dealing with an important part of an actor or political figure’s life, getting a sense of who they were, and then trying to convey that. It’s a question of how you see it! Some photos are posed but most, including some of my favorites at the Andy Warhol: Fantastic! exhibit here in Berlin, are not posed. This one of Andy and Edie Sedgwick is one of the best pictures and it’s totally candid.

You once told a story about how Robert DeNiro drove a cab around New York for a month before filming Taxi Driver, and stayed in character even off-camera. What was it like trying to get candid photos in such a setting?

On a film set, you’re dealing with something that is imaginary to start with. You’re trying to portray either the message of the film, or show what the film is about. When a photo is appearing in a magazine, there is almost no truth to it all. The photographer has a choice: I can do a picture of you smiling, and I can do a picture of you very sad. The photo editor looks at the two pictures, but they’re only going to use one picture to sum up who you are. So I tried to do something where people would look at it and really relate to that person, especially if it was an actor or someone they really cared about. Photography has a way of bringing human interest into things.

In what ways?

We read headlines for things like drought in Africa or something like that but it’s really the photographs which impress us. That’s why LifeMagazine was so successful because it was the photographs that people reacted to much more than the words because it’s easier. You don’t have to really study a headline or an article, you just see it right away.

When did you realize the power of photography as a document rather than as art?

Probably when I started working for Life and started getting assignments with people who were significant in one way or another. There is also a Walker Evans picture of Park Avenue in New York in the 1920s, it is just a view of the street and a parked car. But I’ve always wondered, did he take the picture by accident or did he have a sense that this picture would be very special 50 years later? The way people dressed has changed, the buildings have changed, everything about it… And photography also dictates that for us.

Comments